Death Stranding 2 review – one of the best open-world games ever created

By Kirk McKeand

I feel like Hideo Kojima is winking at me, the scamp. An unhinged Troy Baker wears a red mask as antagonist Higgs. Underneath the mask, clown makeup. He tells me to get ready for “a good old-fashioned boss fight,” before summoning a giant, mechanised squid with glowing weakpoints along its joints. “You like video games in your video games, sir?” I imagine Kojima asking me. “Here’s some damn video game.”

Death Stranding was a difficult game to quantify. It stretched the limits of what a triple-A action game could be with its sedate pace and novel mechanics. Some very loud – and very wrong – people called it a walking simulator due to its focus on making deliveries across vast, Icelandic-looking wilds. There were parts of it I loved – the freeform hiking, the vibe, the music, the world – but the structure, its simple action, and the constant exposition made it difficult to reduce my thoughts to a score out of five at the bottom of 20 paragraphs. After asking myself if I could recommend it to everyone, I went with a three.

To meet Kojima where he lives and get a bit meta with you, I’ll allow you to skip the exposition, if you want. The score at the end of these paragraphs (I don’t know how many yet because I have a lot to say) will be 10 out of a possible 10.

I’m not sure if it’s Kojima or us who can’t let go, but the specter of Metal Gear Solid looms tall over Death Stranding 2. Actor Luca Marinelli plays Neil, who takes on a similar role to Mads Mikkelsen in the first game. He’s a former special forces operative, flanked by army skeletons, who wears a bandana tied around his head like Solid Snake. Neil’s full name is a play on Nirvana – as in the afterlife, not the band – the goal square in an ancient Indian board game called Moksha Patam, which evolved into Snakes & Ladders. He put a legally distinct Snake in a game where you place ladders. Goddamnit.

These are the lengths Kojima goes to. And it doesn’t stop there.

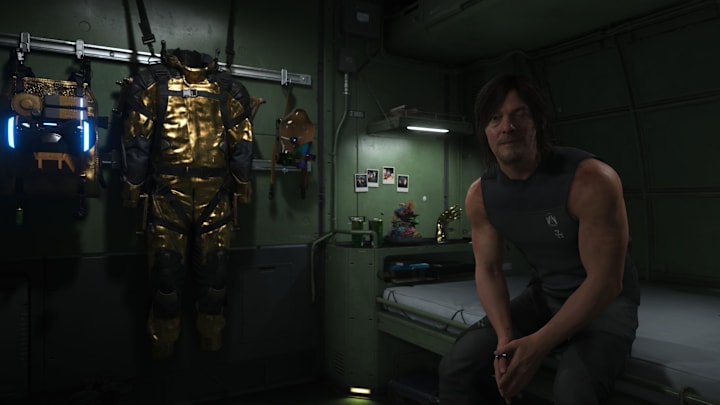

Your mobile base, a tar ship called the DHV Magellan, looks like Metal Gear Rex. Norman Reedus’s Sam uses camouflage and shadows to sneak into enemy bases. A mysterious, Gray Fox-esque ninja rends flesh and removes body parts in a flashy cutscene. Characters talk about phantom pains and missing limbs. Everyone you gather on the Magellan has lost something, but gained each other. A lot of it is subtext, and some of it – the bits I won’t spoil because they haven’t been shown – is just text.

As well as riffing on concepts from The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas with its sacrificial jar babies and being a parody on how social media interactions aren’t a substitute for the real thing, Death Stranding 2’s story is about loss, acceptance, and legacy.

Kojima is holding onto his baby, his “Lou” – Metal Gear Solid – in Death Stranding 2. But is it Kojima’s phantom pain we’re feeling or ours when a character says, “Kept you waiting, huh,” and we get that pang of nostalgia? Did Kojima include all these references and familiar gameplay systems to appease the fans of his previous work or to hold onto what he’s lost? Without asking the man himself, it’s hard to say, but you can feel it, the wink.

There are layers and layers to it. It’s winks all the way down.

After experiencing the COVID lockdowns, Kojima went back and rewrote huge portions of Death Stranding 2, and that context pokes through the skin of the game. Your mobile base is full of life. Companions wave to you as you move between rooms, they take a more active role in the story, and they interact with each other. Sam, now over his fear of being touched, isn’t scared of a warm embrace. Even the holograms you chat with at the various survivalist shelters have more distinct characters, with their own fashion sense, and occasional side stories that lead to unique missions. The first game was sterile and lifeless by design, but this sequel is vibrant and human.

It portrays digital connections as meaningless, satirising the serotonin boost we get from online shares in the form of “likes” from NPCs and other players. The first game did the same, but this recontextualises it after our shared reality of the last few years. When you enter a shelter and you see the signs left by other players, lazily dotted down the slope to ensure maximum engagement as other players pass – a purely selfish act to get more “likes” – you see it for what it is: UGC junkmail, or spam. It makes you appreciate it all the more when another player leaves something useful, be it a structure, a warning, or a footpath carved out from their steps.

Death Stranding 2 tells us upfront that we’ve all developed a form of aphenphosmphobia, a fear of connection. The way we live, we’ve all lost something. We play video games and watch movies to get back to that natural state, to the wilds we originate from, the ones Woodkid sings about in the game’s theme song — a song so key to the game it gets three versions. For all its talk of mothers and babies, it wants us all to reconnect with Mother Nature and the womb of the world by showing us the grandeur and violence of it, and how that vastness makes us feel inside, the way it calls to our soul.

The forecast tells me it’s rainy with a chance of ghosts, but the natural world is just as awe-inspiring and terrifying as the supernatural here. Not only are its Mexico and Australia maps more varied than the first game’s America, but the conditions – whether it be the time of day, the weather, your equipment, or other players’ structures – mean the world is constantly transforming.

Earthquakes buckle your knees and roll boulders down hills. Rain hammers down, reducing visibility, but not as much as the dust clouds from the desert or the whiteouts up in the mountains, where avalanches can sweep you away in a cascade of snow and ice. Heavy rain overflows rivers, destroying misplaced bridges and making crossings more treacherous. Even the current can get you, its strength pushing you into dangerous red areas highlighted by your terrain scanner. Sometimes rivers dry out and allow you to cross with ease if you stay on your toes in case of a flash flood. Thin air at high altitudes can make you pass out unless you invest in an oxygen mask or manage your stamina well. I haven’t even mentioned the wildfires. The elements are more of a threat than the ghosts and paramilitary outposts dotting the landscape.

In the first game, most of the friction was theoretical. You could see what Kojima Productions was aiming for, but it wasn’t tuned right. I rarely destroyed cargo in Death Stranding, but the sequel makes every journey perilous. Even dunes become dangerous when a sandstorm rolls in, forcing you to rely on your scanner so you don’t fly over them at too high a speed in your truck or tri-bike, wrecking the cargo on the landing. A simple rock can ruin your haul if you’re driving carelessly. The vehicles feel much better this time around, too, making their way over insignificant bumps and rocks instead of catching on every little fold of earth like a forklift with the forks down.

You feel the aftereffects of every environment you’ve visited, reminding you of your ordeal and anchoring you in the fantasy. After the dunes, specs of sand flick from Sam’s backpack as he takes it off. His face gets red and peely from sunburn. Tar and blood coat your gear. Snow sticks to you and melts off, and your fingers and toes blacken from frostbite. Out in the world, there are some lovely animation touches, like how Sam shakes out his arms and flexes his fingers to stave off numbness, adjusts the cargo on his back, and shivers in the cold.

Jungles, deserts, canyons, ashen flats, shrubland, snow-topped mountains, ruined cities filled with fossilised skyscrapers; Death Stranding 2’s world is packed and varied. It solves the issue of the first game’s finale – which forced you to backtrack the entire route but ruined all the logistical building work you did along the way with plot contrivances – by keeping you in the same large play space for most of the game, tweaking zipline placements, bridges, shelters, jump ramps, and more until you optimise every route because you’ve seen it from every direction.

You don’t just zoom through these areas on the way to the next. Even if you plan to mainline the game without taking on sub orders – I got five stars in every location and spent 120 hours doing it because it’s so excellent – you’ll constantly retrace your steps because of the genius, cohesive map design with its soft gates and invisible finger nudging you along while still giving you total freedom. But even with that familiarity, it doesn’t lose its wonder.

It isn’t the largest world map ever created, but every single mountain is placed with intention, hiding any limitations you might otherwise see. Your slow speed through the world, at least in the early game, makes you feel swallowed by the vastness of each area, all that negative space, and the shifting time of day and weather make sure it always feels alien.

When the sun sets on the plain, it turns distant mountains into shadow temples standing in the void against a deep blue sky salted with cosmos. You desperately clamber across ridges like a goat, rain hissing and falling like the tendrils of the Stranding in the blind night land, led by torchlight, the distant player structures lit up in sci-fi primaries, your only sense of life. Up in the snowy mountains, chiral clouds obscure the ground, stretching out in a fluffy blanket as an impossibly large moon dominates the sky and lunar light dances along the snow in a trail of heavenly glitter. It reminds me of how Cormac McCarthy paints the American wilderness in Blood Meridian as this almost cosmic, ethereal space in the wild minds of those lost in it.

In most open-world games, you can smell the procedural art tools, but every inch of this feels authored — every crag and nook, every stream and mountain pass. A lesser game with topography this complex and unpredictable would have an unstick button in the pause menu, but Kojima Productions has scoured over every inch of this world to make sure it’s navigable and plugged up. It’s an incredible achievement, and one of the most beautiful, striking, and surprising video game worlds ever created.

The way you navigate the world evolves as you play, too, each connection level with each outpost granting you a new, sometimes game-changing piece of gear. I won’t spoil, but there are an intimidating number of ways to speed up deliveries with smart equipment use. There’s depth to every single system, and most things have multiple uses. A tranquiliser gun is handy for a sneaky infiltration, but it’s also really good at knocking koalas out of trees to fill up your animal sanctuary in Death Stranding 2’s animal conservation minigame. The controls have lots of depth, too, like how you can specifically sidestep in any direction while hiking to navigate rough terrain, or how you can move the stick when exiting a vehicle to disembark on a specific side. The haptic feedback and fine control remind me of the attention to detail of the cars in Gran Turismo, applied to human kinematics.

Even your backpack can be used tactically now. You can take it off completely, along with your cargo, to get light on your feet for a fight or stealth, but you can also use it as a honeypot to lure in enemies. When stealth fails, there’s a range of useful, non-lethal firearms and throwables to use, and even hand-to-hand combat is expanded with dodges, blocks, and counter attacks, as well as melee weapons and special, pizza-based martial arts moves because Death Stranding 2 is even more weird than the first game (complimentary). Or you could find a perch, judge the distance, and pick them all off with a sniper rifle. Or drive in with a weapon-mounted truck. Or call in an artillery strike. Or distract them with fireworks. Or slip past. Or…

Stealth in the first game existed, but it was neutered by the fact that enemies could just scan you, immediately revealing your position. That’s gone now, giving you a proper stealth and action sandbox to play around in between deliveries. It’s still a game about being a courier in the apocalypse, but there are flashes of Metal Gear Solid V’s slick, open-ended gameplay now, too. Another little wink.

When the weather forecast tells you it’s ghost time, BT encounters are much more transparent. While BTs would only be visible when you remained stationary in the first game, you can see them consistently within a certain range while moving slowly in DS2. This means instead of playing a game of change direction when your scanner gets hyperactive, you’re now cutting through their territory with the threat of capture looming over you, which not only makes it feel better in play, but also makes it more tense. It’s bumped up more with Gazers, a new type of BT that don’t just sense movement and sound — these can see you, their screams are terrifying, and the sky turns blood red whenever you find yourself in their territory. Like everything else in the game, your relationship with BTs evolves as you progress and learn what you can get away with, but that process is rewarding and full of hard lessons. You start slow and careful, learning when and how to speed up and take risks as you unlock better gear and build an understanding, or mastery, of the world and systems.

While it’s still a slow-paced, methodical game, it respects your time much more than Death Stranding. Every piece of terminology is added to a corpus that you can browse whenever you want, and almost every bit of non-critical exposition is optional. Entire cutscenes are hidden away as a reward for curious players. No one calls you up to give you a monologue on the Magna Carta or quantum physics. Even using the shower is now one single prompt instead of three separate ones for various bodily functions.

When you are treated to a cutscene, they’re some of the best-directed, well-framed, and stylish Kojima has ever produced. Fragile catching a passing ember on the end of a cigarette to light it, the way the camera cuts low to capture a bike crash or pans for the perfect angle during the excellent fight choreography — it’s slick and brilliant. While many of the more famous actors have quite subtle performances compared to the standout derangement of Troy Baker’s Higgs, it suits their characters and makes the moments where they do crack even more powerful. They’re allowed to be broken and vulnerable. They laugh and cry and sing. They just ring more true as humans with proper bonds. Their performances are helped along by some of the best character models ever rendered, right down to their gooseflesh in the cold, or how they lick their dry lips for moisture so Kojima Productions can show off how wet and fully modelled the inside of their mouths are.

Every single criticism I had of Death Stranding has been addressed, allowing this sequel to show the full genius of Hideo Kojima’s vision. His favourite music, the recurring themes he explores, his famous friends, the tribute to Low Roar’s late frontman Ryan Karazija, the nods to his previous work, the post-COVID anxiety imbued into the story, and even the Kojima-made trailers leading up to release – playing Death Stranding 2 feels like making a personal connection with the man himself. He’s reaching out his hand from the other side and there’s little you can do but grasp it. You can feel the brush strokes, and now and then, that wink. A Hideo Kojima wink.

Death Stranding 2 review score. 10. Open-World RPG. PS5. Death Stranding 2: On the Beach

feed